Who Was Prepared For This? – Property Insurance and Civil Unrest

For November are featuring an article from Best’s Review. Reach out to keep the discussion going.

Civil Unrest

Who Was Prepared for This?

KATE SMITH – NOVEMBER 2020

RIOT RECOVERY: Cleanup begins in the streets of Minneapolis after protesters damaged and looted businesses in the wake of George Floyd’s death on May 25. Floyd died while being restrained by Minneapolis police officers, sparking nationwide protests and, in some locations, riots.

AP Photo/Julio Cortez

Key Points

- Mass Discontent: More than a quarter of the world’s countries saw a dramatic rise in protests last year.

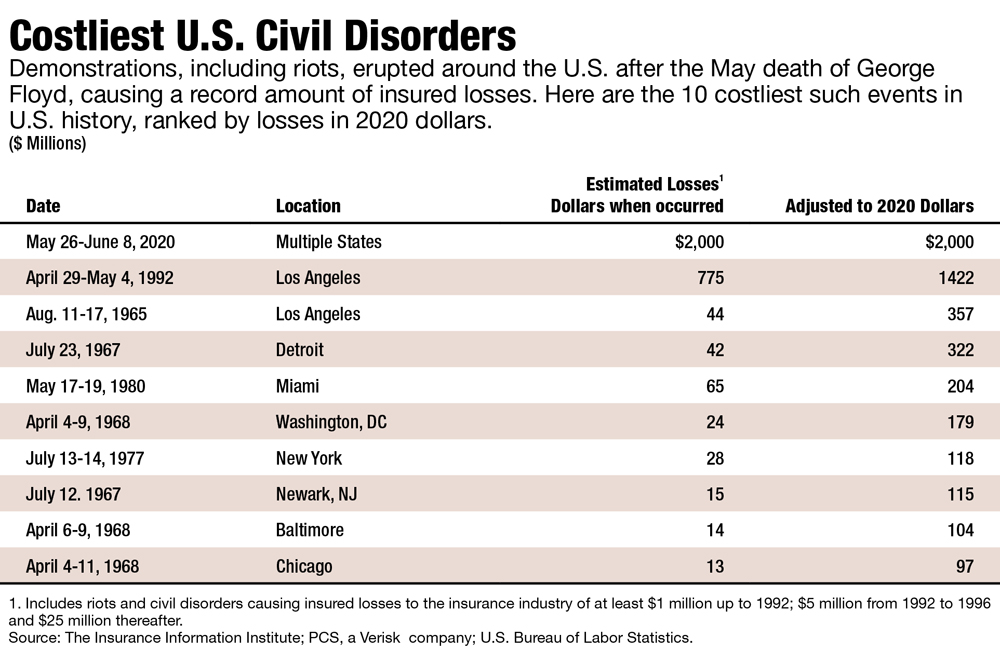

- Record Losses: The riots following George Floyd’s death caused more than $2 billion in insured losses, a U.S. record for civil disturbance.

- New Criteria: Underwriters are paying close attention to election cycles and whether businesses are associated with anything unpopular.

On Day One of the riots that followed George Floyd’s death, Dawn D’Onofrio’s company received a multimillion-dollar claim. Then came another one, from a completely different city in a completely different region of the country.

“That really got our attention,” D’Onofrio, the president and CEO of WKFC Underwriting Managers, said. “The claims were absolutely staggering. There was no way an underwriter would have foreseen those circumstances.”

2020 has been full of unforeseen circumstances for property insurers. There was the start of a global pandemic, more hurricanes than alphabet letters and West Coast wildfires so vast that their smoke tinted East Coast skies—not to mention derechos, tornadoes and convective storms.

On top of that, there were more riots and civil commotion than the United States has ever seen.

Between May 26 and June 8—the two-week period following Floyd’s death while in custody of Minneapolis police officers—demonstrations and protests erupted in more than 40 cities across 20 states. Some of them turned into riots. Insured losses from those events surpassed $2 billion, topping the 1992 Los Angeles riots as the costliest civil disturbance in U.S. history.

“Who was prepared for rioting and protesting as we have witnessed throughout many cities in the U.S.? It has been unexpected and extreme,” Brenda Austenfeld, president of national property for wholesale broker RT Specialty, said.

While the United States has seen riots and looting over the years, such as Baltimore in 2015, none rose to the magnitude of 2020. Violent demonstrations spilled into the summer and carried through to the fall. And with U.S. elections slated for this month, there is no end in sight.

“We see the election as a point of interest relative to riot and civil disorder risk; roughly half of the country will be angry either way,” said Tom Johansmeyer, head of PCS, a Verisk company.

The troubles are by no means confined to the United States. Violent demonstrations are on the rise globally. According to the 2020 Verisk Political Risk Outlook, 47 countries—which equates to more than a quarter of the world’s countries—saw a surge in protests in 2019.

“If the early 2000s were marked by the global war on terror, the 2010s by post-crisis economic recovery and the rise of populism, the 2020s appear set to become the decade of rage, unrest and shifting geopolitical sands,” Verisk wrote in its report.

France, Hong Kong and Chile are among the most notable examples of recent costly protests. The French “yellow vest” protests caused roughly $90 million in insured losses, while protests in Hong Kong cost $77 million and unrest in Chile cost $2 billion, according to Allianz Global Corporate Specialty.

“The magnitude of the events is increasing,” said Bjoern Reusswig, head of global political violence and hostile environment solutions for AGCS.

In the United States, PCS declared the post-George Floyd riots the first multistate civil disorder catastrophe. By contrast, the L.A. riots, which occurred in the wake of Rodney King’s arrest and beating by Los Angeles police officers, were contained to one city. That event cost the insurance industry $775 million ($1.4 billion in today’s dollars), according to the Insurance Information Institute.

Loretta Worters, spokesperson for the III, said this year’s riot-related losses pale compared to hurricane losses. But when viewed in the context of an already challenged property market, they are significant.

“It’s the confluence of events,” Worters said. “It’s not just riots. It’s not just a pandemic. It’s not just a hurricane. It’s not just a wildfire. It’s that all of these issues are coming into play at the same time for property insurers.“

The riots are one additional pressure point.

“It’s been death by a thousand cuts for most property insurance carriers in 2020,” Rick Miller, U.S. property leader at Aon, said. “That’s the environment property insurers are doing business in.”

The amount of work an underwriter puts into an account is, by far, more than double than it was a year ago. …They have to underwrite the city, the municipality, the town, and know whether the police are responding to calls or the fire departments are not going out to fires.

Dawn D’Onofrio

WKFC Underwriting Managers

U.S. Market Changes

In the United States, losses from strike, riot and civil commotion are typically covered under property insurance policies. Though these are well-known—and named—risks, they have not been a high priority for property underwriters.

“A couple years ago, riot was likely not at the top of an underwriter’s checklist when they were reviewing a particular account,” Miller said. “Now it is.”

The widespread unrest has caused U.S. property underwriters to pivot. They are asking more questions, reviewing different information and doing more legwork to determine clients’ exposures.

“The amount of work an underwriter puts into an account is, by far, more than double than it was a year ago,” D’Onofrio said. “They’re looking at crime scores, looking at migration of the homeless, vacancy rates. They have to underwrite the city, the municipality, the town, and know whether the police are responding to calls or the fire departments are not going out to fires.”

Some fire departments, she said, have chosen to let buildings burn rather than risk firefighters’ lives by sending them into riots. “The day-to-day underwriting has increased exponentially since a year ago because we have to consider all this new information.”

Property underwriters are also examining whether mobs might target particular insureds.

“If there’s a storefront or an office building with an attractive business or name on it, that is a definite attraction to a mob,” Miller said.

In the commercial property segment, underwriters have taken a targeted approach, identifying accounts and risks deemed to be most susceptible to riot, such as a large pharmacy chain or a large retailer with products that could be attractive to looters.

“It’s not just about whether you’re in an urban area,” said Patrick Mulhall, executive vice president of commercial property for U.S. insurance at Sompo International. “There are industries that are more vulnerable to these perils than others. Commercial real estate comes with some of that. There’s retail and subsectors of retail—pharmacies, specialty clothing companies, high-value merchandise stores.”

With the 2020 riots, most of the impact has been on retail and real estate risks with urban risk concentrations, Miller said.

That was particularly true in the riots associated with Floyd’s death. In that event, “one-third of the industry insured loss so far has come from three national retailers,” Johansmeyer, of PCS, said.

The effect, however, has been felt by “all size business,” RT Specialty’s Austenfeld said. “It’s just a matter of how significantly.”

Even at the mom-and-pop shop level, premiums are rising.

“Across the board we’re seeing rate increases,” said D’Onofrio, whose program insures 8,000 policies of Main Street America-type businesses. “In certain areas where the crime scores are higher and there’s a known riot exposure—for instance in high-profile metropolitan cities—we can name our pricing and terms, if we are comfortable insuring the risk.

“A year ago, we would have freely written metropolitan business all day long. Now we go in very cautiously and we tell businesses, ‘We can do it, but it’s going to cost significantly more and you need to have skin in the game.’ They have to have a very high deductible and take ownership of protecting their property.”

Aon’s Miller said some markets have looked to exclude SRCC (Strikes, Riots and Civil Commotion), but that’s not rampant. “The biggest change,” he said, “is on the retention or deductible front for businesses deemed to be at higher risk.”

Austenfeld said the excess and surplus (E&S) segment has seen an increased flow of business as standard lines tighten terms and insureds look for greater flexibility in building coverage.

“Many times an underwriter, especially in the E&S world, will increase the deductible specific to this segment—rioting, civil commotion or malicious damage,” Austenfeld said. “We can be more creative in the E&S world with freedom of rate and form in the nonadmitted arena. If there is a single peril causing more frequent losses, we create a solution for our retail client trading partners by a specific deductible area versus changing the entire coverage for an insured.”

Many times an underwriter, especially in the E&S world, will increase the deductible specific to this segment—rioting, civil commotion or malicious damage. We can be more creative in the [excess and surplus] world with freedom of rate and form in the nonadmitted arena.

Brenda Austenfeld

RT Specialty

International Affairs

Outside the United States, strike, riot and civil commotion coverage typically falls upon the specialist market, with coverage often coming through political violence policies, Reusswig said. Until recently SRCC was a secondary concern, behind terrorism, for those underwriters. That’s changed over the past two years, though.

“Fortunately those big-scale terrorist attacks are going down in number and in severity,” Reusswig said. “So now we have to change our approach because we see, on the one hand, sizable terrorist attacks going down, but SRCC events are definitely going up.”

That shift began in late 2018 with the French “yellow vest” protests, which originated in response to higher fuel taxes. In 2019, a proposed extradition bill spurred demonstrations in Hong Kong, which quickly escalated to violence. And in Chile, a 4% hike in public transportation fares kicked off months of riots that caused billions in damages.

As in the United States, international insurers have responded to the uptick by increasing rates and changing terms, particularly for certain sectors and geographies.

“The one thing that stands out about Chile and the U.S. is the disproportionate impact the retail sector felt,” Johansmeyer, of PCS, said.

A chain of supermarkets in Chile, for example, would now pay much more in premiums than a few years ago, Reusswig said. And certain retail businesses will have a harder time finding appropriate limits.

“If you are a retail chain or a high-end retailer, which makes you attractive to looting, then there will be capacity and pricing issues,” Reusswig said. “If you’re a Chinese bank in Hong Kong with retail offices on the ground floor, you will have issues. If you are a Chinese investment bank with offices on the 52nd floor of a high-rise building, you probably won’t feel the impact on the pricing or the capacity side.”

Underwriters also are examining new factors to their evaluation of a risk.

“We now pay a lot more attention to elections,” Reusswig said. “Elections are one of the main contributors to public unrest. We look at whether a general election or federal, state or municipality-level election is coming up in specific countries that have a track record of protests following elections. That’s now absolutely part of the underwriting process.”

They also look at whether clients are associated with anything unpopular. “There was a Chinese cell phone retailer that was completely looted in Hong Kong,” Reusswig said. “And there was a non-Chinese cell phone retailer directly next to it that didn’t have a scratch on their windows. The fact that the company was associated with China was enough for it to be raided.”

Aggregation Risks

Across the globe, the rise of civil unrest is causing aggregation concerns.

While underwriters long have looked at aggregations regarding natural catastrophes, riots are now in the consideration mix.

“If you are a large national retailer with multiple locations in a particular city, underwriters will review that risk accordingly,” Miller said. “You are now looking at the possibility of multiple facilities being impacted by the same event, making it more of a catastrophe versus risk event.

“A risk event would be a fire, which generally would impact a single location. Riots might not be quite as widespread as a hurricane, but they can involve multiple locations of a schedule of locations. Going forward underwriters will view the risk of riot differently. Losses and the causes thereof, change how underwriters review accounts and impact what an underwriter is willing to offer and charge for assuming that risk.”

In addition to controlling aggregation on this peril, experts also are looking for ways to better predict events. Some say the Gini coefficient, which measures the disparity of income in the country, is helpful. Others say the perceived corruption index is a good benchmark, as displeasure with government is a main contributor to civil commotion.

“You could easily find another half dozen indicators,” Reusswig said. “But combining them, and being confident that the countries coming out of this process are those that you actually should watch going forward, that’s still an ongoing process. No one has found the golden goose yet to solve this issue.”

Kate Smith is managing editor of Best’s Review. She can be reached at kate.smith@ambest.com.